Film

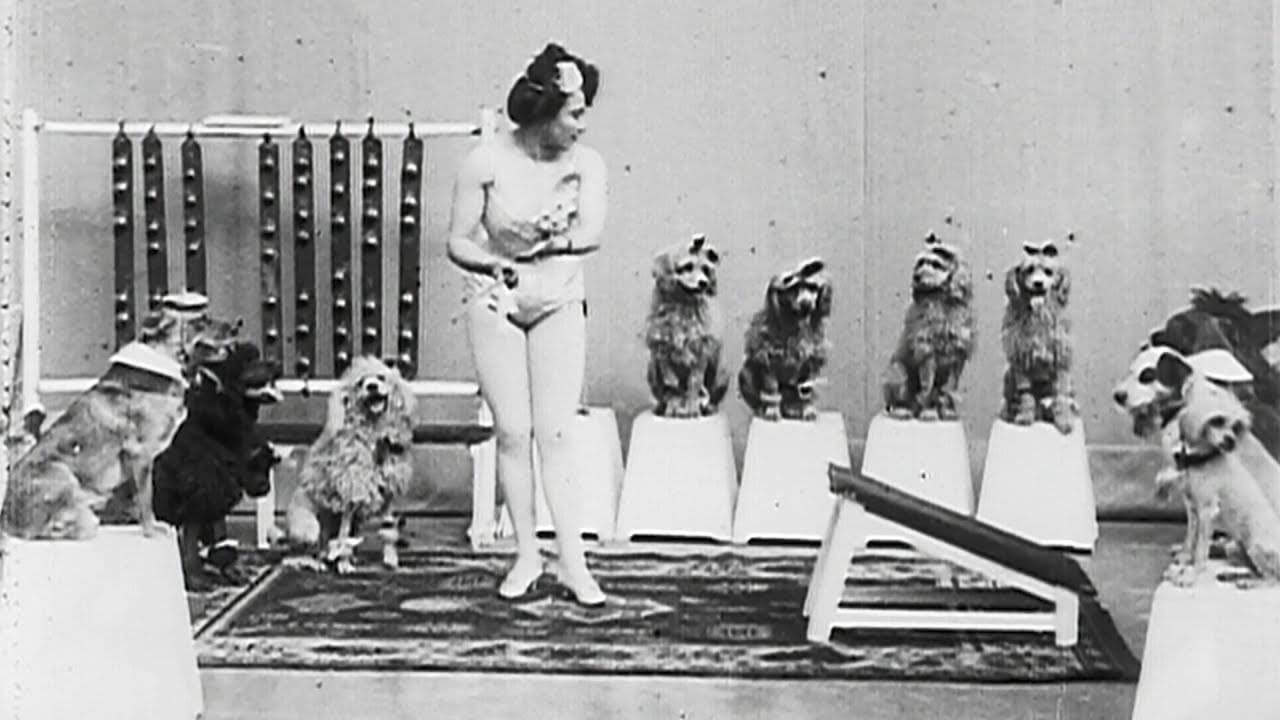

"Les chiens savants," or "Miss Dundee and Her Performing Dogs" (1902)

Watch a lot of golden-age films and you weave a tapestry in your head of lifespans and career dates. You find yourself looking up how much too old for Kim Novak Jimmy Stewart was, and you add that to the reasons that Judy should simply walk out rather than put up with Scottie's nonsense. You watch Edmund Gwenn and marvel that in 2025 you're watching gorgeous Technicolor footage of a man born in 1877 and feeling a warmth that's kin to love. You watch The Misfits and lament the lives cut short by the various pathologies of midcentury American success. Look backward at culture as much as I tend to, and time and mortality are constant companions.

Animals on screen elicit similar thoughts, but with a more poignant edge. To overstate for effect: Almost no matter how recent the film is, they're all dead. The lifespans of domestic animals are so short relative to ours. Sandy Duncan is still with us, but the cat from outer space beamed back up ages ago. While the relatively long-lived Skippy starred in four Thin Man movies, Buddy, the star of Air Bud, didn't even live to see Air Bud: Golden Receiver the next year. If one of the Queen's corgis had out-auditioned Sean Connery in 1962 we'd be on our 27th canine Bond by now. Animals just aren't with us that long.

Except, well, there they still are, on screen. Like the fin de siècle dogs whose dexterity and skill were captured by Alice Guy-Blachè in 1902 in this delightful short film.

It's as simple as its title. Miss Dundee, a young woman in a leotard and heels, leads a dozen or so dogs through a set of tricks and feats. Some poodles jump over a raised baton. A Great Dane surprises us by entering the frame and doing the same. The poodles weave in and out of the Great Dane's legs like stairclimbers in an Escher painting. There's some more jumping involving ladders, which by the end is truly impressive.

No circus act would be complete without a clown, and we get one here, a mutt in a tailcoat who refuses to perform, until that very refusal is deployed in what it's only fair to call a plot twist, one that culminates in a properly funny performance featuring a dog in widow's weeds.

It's completely silly, and nicely pure. Unlike most animals, dogs, bred for millennia to respond to humans, enjoy having jobs and performing tasks well, and it's fun to see them at work.

And . . . what a gift even to see them at all, plucked out of 1902, these dogs who were probably gone before World War I, these dogs who were probably someone's best friend, these dogs who had no idea on that day that the routine they were running through was any more special than any other performance they'd given. I hope they got extra treats that night. They're good dogs.

Music

Traffic from Paradise (1993), by Rickie Lee Jones

It's no insult to say that when Rickie Lee Jones first appeared on the scene, she was doing a bit. It was a good bit, and it was different from any other bits going. Her friend Tom Waits was doing a not-dissimilar one, but while his had roots in poetry and saloon sounds, hers was more linked to jazz. (It's no surprise that she's the one of the pair who's recorded a lot of standards.) And gender itself, for the Beat-inflected, is a real differentiator.

Plus, she was good at it. Even if you can't figure out half of what she's saying the first few times you hear "Chuck E.'s in Love," it's catchy enough to stay with you, and once you decipher the lyrics, its twist ending is sweet enough to make you like it even more. You can see why it reached #4 on the pop charts, the only time she'd get higher than 40. (Waits has never charted.) The rest of her 1979 debut album is full of jokes and slang and posturing, mid-century outcast life filtered through '70s permissiveness, but with the help of a crack band she puts it across through her voice, whose melodic and dynamic range at that moment seemed all but limitless.

In commercial terms, it was all downhill from there. Her next album, Pirates, would crack the top 10, but nothing else came close. At the same time, each album offered something different, unexpected. Piano-driven story songs. A Western-inflected album with a Don Was–supplied pop sheen. Even a trip-hop album. There's something to recommend them all; they're the work of an artist who is always looking for something new.

This is the one I come back to. Released in 1993, when Jones wasn't yet forty, Traffic from Paradise feels like the work of an older artist. It's a quiet, acoustic album that's suited for fall, when we're watching the year fade, wondering where it went, and thinking back on what we've done with it.

The record opens with a quartet of songs that are, broadly speaking, about regret and loss, about things we failed to do, sources of shame. There's religious imagery, and some hints that we might be accepted, sins and all, but the comfort is far from sure. Regardless, there's beauty. "Stewart's Coat" in particular makes the most of Jones's deeper, more controlled middle-aged voice, pairing it with a repeated acoustic guitar figure in a way that still gives me shivers after thirty years of listening.

Then the tone and rhythms shift, and joy, tempered, but there to be grabbed onto, enters the picture. I love "Jolie Jolie," a gentle rave-up with elements of zydeco, but it's her cover of "Rebel Rebel" that's the standout here. Bowie's original is determined and defiant, its protagonist's brashness admirable, but we can't help but think that, as the English say, there'll be tears before bedtime. Jones's version replaces defiance with confidence; there is joy in this song.

The final trio of songs both sound and sing of redemption and recovery. Even here, it's not certain, and loss is never far. The syncopation of the middle section of the album is mostly gone, replaced by what would be stateliness if it weren't so welcoming. Leo Kottke contributes such gorgeous backing vocals and guitar to "Running from Mercy" that platitudes like "Little acts of kindness and little words of love / Make our earthly home like heaven above" feel genuinely bracing.

By the time we reach the closing track, "The Albatross," which opens with Jones and David Baerwald singing "There, there is my ship / finally come in. / I see the mast / rolling on the steps / over the garden wall," we believe they believe it. This is music that feels hard won from life, that helps us close old chapters and look forward to new. The final lines of the album pop into my head frequently, and even to this unbeliever they're comforting every single time:

Here, here's where we live

Here is a sea, my family

We'll always be young as we've ever been

Death will not part us again, nearer to heaven than

Ten thousand ancestors who dream of me

Well, I hear you dreaming of me

Yeah, sometimes, dream of me.

Book

The House That George Built: With a Little Help from Irving, Cole, and a Crew of About Fifty (2007), by Wilfrid Sheed

"It me," I say with only slight exaggeration–but replace Led Zeppelin with the American Songbook, and "just discovered" with "returned to." I've loved that legacy since I was seventeen (and a Zeppelin fan) and first listened to the soundtrack of When Harry Met Sally. It felt like Harry Connick, Jr. was introducing me to unknown lands, full of treasure. A college friend connected me with Sinatra, and the best of the popular songs of the 1920s to the 1950s have lived in my head ever since.

Lately they're taking up more space. Most of that is because of my increasing engagement with the piano, which has given me insight into how these songs work and made me want to know more. I play classical for technique; I play standards for pleasure. They've also claimed a larger amount of my listening time than ever, as I've spent the past couple of years expanding my knowledge of mid-century singers beyond the most familiar monuments. I find that what I want now—as I cook, as I wash dishes, as I read—is what a couple of generations ago was thought of as adult music, music that aims at beauty and sophistication and frequently hits.

As the Onion knows, when you're deep in a cultural obsession, you want to talk about it. Stacey is kind enough to put up with some of it, and I have friends, IRL and online, who are happy to join in. But no one wants to hear about it all the time.

Which is where Wilfrid Sheed comes in. This book is that conversation, one that seems to have begun for him when he was ten and saw Oklahoma during its first run. The House That George Built asks journalism's old Five Ws, but it does so not to build a history but rather to stock a store of anecdotes and appreciations. And he adds a sixth, a suitably awe-struck "How?" If you want fusty, detailed examinations of these songs, Alec Wilder is there for you. This is different. "The proper medium for studying the American song," Sheed writes, "is, after all, neither the lecture nor the library but the sing-along and the rap session."

There are drawbacks to that approach. Chattiness can become confusing digression. Jokiness rears its head, with only intermittent success. Chronology can be slippery. Knowledge of events and gossip is sometimes taken too much for granted, leaving us at sea. I wouldn't want to go to court with a single detail from the book without corroborating it. Sometimes we want Sheed to get on with it all.

But, as Donald Westlake wrote of a plot hole in a Nero Wolfe story, no matter, no matter. We know what we're here for. We're here to listen to someone who loves these songs as much as we do and knows them and the milieu from which they emerged far better. We're here to learn from him that Harold Arlen told him that "Stormy Weather" was "a throwaway. He wrote it first, and found out why years later." To have him praise Hoagy Carmichael's "collector's item of a voice." To have him tell us, as we nod in agreement, that Jerome Kern's music "leaves one feeling not just good, but noble." To have him analyze the team-up of Fred Astaire and Irving Berlin that changed everything:

It's as if Astaire's sense of the sounds he wanted and Berlin's sense of Fred's essence, his image, added up to a third personality, a city boy harnessed to a country boy in the cause of that magnificent anomaly, American sophistication.

If love is attention, these insights are its product, and once he's shared them they're ours, too, to stay with us and help us generate new thoughts of our own about these endlessly rewarding songs.

Plus, Sheed–as you'll also see if you read his novels or other nonfiction–delights in turning a phrase. Some favorites from this book:

He was in his mid fifties now, an age when the waiter looks over every few minutes to see if you’ve left yet.

This is sophistication for the masses, well within the reach of a bright traveling salesman.

Scat is simply jazz’s way of saying, “Get lost.”

The role of an American upper class has never been that clear to most people anyway, but one of its functions has always been to be laughed at.

World War I had done its extremely modest bit to bring Americans together.

If you love these songs like I do, like Sheed does, like people the world over have done for almost a century now, this book is for you. A hundred years ago, they started writing songs of love, and they're for us.

Poetry

"Jolly Good Ale and Old," by William Stevenson

I'll attend my last regular-season games of the year at Wrigley this weekend, and because one of life's great pleasures is drinking a beer at the ballpark, I'll close with the final stanza of this sixteenth-century poem.

Now let them drink till they nod and wink,

Even as good fellows should do;

They shall not miss to have that bliss

Good ale doth bring men to;

And all poor souls that have scour'd bowls

Or have them lustily troll'd,

God save the lives of them and their wives,

Whether they be young or old.

Back and side go bare, go bare;

Both foot and hand go cold;

But belly, God, send thee good ale enough,

Whether it be new or old.