Having spent time the past few weeks thinking about your friends and family, every person on your holiday gift list, I present the following, ready to clip and take with you to the shops this weekend.

I’ve stuck to books because we can’t count on recipients using physical media for movies or music. (If they do, get them the Ranown Collection box from Criterion! Or Hundreds of Beavers! Or the new expanded edition of The Disintegration Loops!)

Typically gift guides focus on new products. But anything can be new for someone who’s not seen it before, and while the past is, we can’t deny, mostly horrors, it does hold treasures. I also offer alternatives, in case I’ve pegged this person so well that they’ve definitely already got the suggested gift.

Let’s get to it.

For your weirdest friend

Stevie Smith, All the Poems (2016)

Biographer Hermione Lee chose a word Smith uses a lot, “peculiar,” as the best to describe her. She’s not wrong. These are short poems, written in plain language and always accessible. But none of that keeps them from being strange, distinctive expressions of a unique experience of the world. Smith told Penelope Fitzgerald that she “must stay unhappy to write poetry,” and the poems can be mordant, even death-haunted. But they’re also funny and clever.

But here in my head I sometimes hear the soft tune

Of the belfry bats moaning to find some more room.

“The world is come upon me, I used to keep it a long way off,” opens “The Deserter.” This book is for your friend who nods ruefully at that line.

Alternative: Zachary Schomburg’s Scary, No Scary

For your friend whose every third text is gossip

Pierre Cholderlos de Laclos, Les Liaisons Dangereuses (1782)

This isn’t a novel about gossip, per se. But it is about one of the core components of gossip, which is—to steal my wife’s description of the film It’s a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World—awful people doing awful things. To read Dangerous Liaisons (as English-language versions are titled), you need a strong stomach for genuinely bad behavior. Two libertine liars lie to each other and plot destruction, only to get destroyed themselves. We’re not talking de Sade here, but nonetheless this is many degrees more heedless and violent than, say, Nuzzi-Lizza. Baudelaire believed that its depiction of the amoral aristocracy helped bring about the French Revolution. Amoral aristocracy, you say? Why does that feel so familiar . . . ?

Alternative: John Aubrey’s Brief Lives

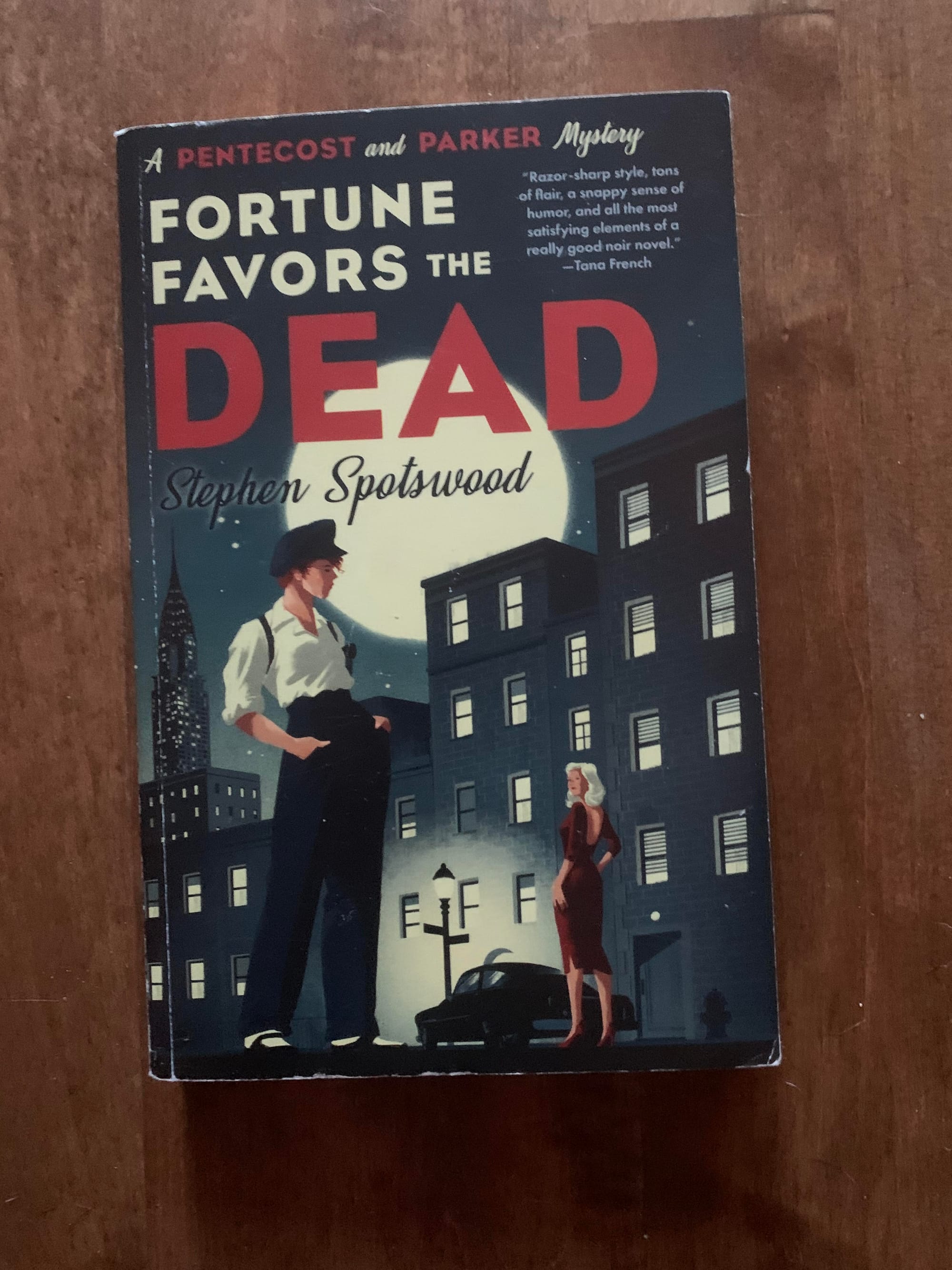

For your friend who has run out of Nero Wolfe stories

Stephen Spotswood, the Pentecost and Parker series (2020–present)

There is no solution to the problem of a finite number of Nero Wolfe stories. They are sui generis. Nothing is as good.

While acknowledging that, the distaff version of the template that Stephen Spotswood offers in this series is engaging and satisfying. Wolfe’s role is taken by Lillian Pentecost, Archie Goodwin’s by Willowjean Parker. The duo solve crimes in postwar New York while building the relationship that in the Wolfe stories we only see long after it’s established. The period detail is fun and mostly convincing, the secondary characters and plots are well imagined, and the development of Pentecost and Parker’s relationship through five books is believable and compelling. You want to spend more time with these people, which is the primary requirement of a cozy mystery series.

Alternative: Ellis Peters’s Brother Cadfael series

For your mom who loves a weirdo (YMMV)*

Claire Hoffman’s Sister, Sinner: The Miraculous Life and Mysterious Disappearance of Aimee Semple McPherson (2025)

I love biographies, and this is a type I particularly appreciate: The life of a figure who was once a household name and now is largely forgotten. Add to that a well-handled account of the complicated details and many characters involved in evangelist Aimee Semple McPherson’s bizarre “kidnapping” and return, and you’ve got a nicely dramatic book about a truly odd person.

*Your mom may vary.

Alternative: Charles Portis’s Masters of Atlantis (YMMV)

For your friend who you call when the heist goes sour

St. Clair McKelway’s True Tales from the Annals of Crime and Rascality (1950)

St. Clair McKelway was a New Yorker staff writer who never quite broke through to general familiarity the way some of his 1930s and ’40s peers did. These days, his only work that’s in print is his war reporting, collected in Reporting at Wit's End. That volume is centered on a long, deliberately calm account of his midwar breakdown as he experienced it moment by moment. It’s stressful but hard to stop reading.

This volume is closer to pure fun. McKelway writes here about people playing modest roles in crime or the justice system. Most of the people in the book, McKelway writes, “seem to me to have been guilty of rascality rather than criminality.” There’s an embezzler, an arson inspector, a corrupt union official, a process server. The best piece is “Mister 880,” the story of a counterfeiter who vexed the T-men for years as he passed extremely crude forgeries . . . of $1 bills. It was made into a charming movie starring Burt Lancaster and Edmund Gwenn.

Alternative: Donald Dunn’s Ponzi: The True Story of the King of Financial Cons

For your friend who loved I Capture the Castle

Joanna Quinn’s The Whalebone Theatre (2022)

This novel got a fair amount of coverage and sold well, but I didn’t encounter it until I was browsing Daunt Books in London last year. (RIP mass culture, 1920–1999). It’s a big family saga of the twentieth century, of the sort that all too easily can slip into sentiment, wish fulfillment, and ahistorical nonsense. Joanna Quinn somehow manages to almost entirely avoid those pitfalls. Are we supposed to love these characters, and does Quinn work to make us do so? Certainly. In 2025, can we really construe that as a fault?

The Whalebone Theatre is the kind of novel you dream of opening at the start of a long flight, a book that will hold (and repay) your attention for hours. It’s no I Capture the Castle, but what is?

Alternative: Rebecca West’s The Fountain Overflows

For your friend with whom you have a two-person book club

Samuel Richardson’s Clarissa (1748)

In late 2016, Stephanie Insley Hershinow told me that Clarissa, Samuel Richardson’s brick of an epistolary novel, takes place over the course of a single year, beginning in January, and thus can be read that way, reading each letter on the date it carries. I did that, with pleasure, and I recommend it to you.

But perhaps William Hazlitt’s opinion might carry more weight?

I consider myself a thorough adept in Richardson. I like the longest of his novels best, and think no part of them tedious; nor should I ask to have anything better to do than to read them from beginning to end, to take them up when I chose, and lay them down when I was tired, in some old family mansion in the country, till every word and syllable relating to the bright Clarissa, the Divine Clementina, the beautiful Pamela, “with every trick and line of their sweet favour,” were once more “graven in my heart’s table.”

The first letter is dated January 10: “I am extremely concerned, my dearest friend, for the disturbances that have happened in your family . . . ”

Away you go!

Alternative: Anthony Powell’s A Dance to the Music of Time

For your friend who enjoys reading about people endangering themselves through travel

Christiane Ritter’s A Woman in the Polar Night (1938)

In 1933, when she was in her early thirties, Austrian painter and writer Christiane Ritter joined her husband for the winter in Svalbard, where he’d gone as part of a scientific expedition and then stayed as a fur trapper. She lived with him in a tiny cabin, in a landscape that, on arrival, she writes, “with the best will in the world I can find . . . neither beautiful nor gripping.” The winter is unbelievably hard, cold, and dangerous. Seal hunts on cracking ice are described in terrifying fashion. The isolation and deprivation are almost incalculable. A hunter who shares their hut says, “Perhaps we haven’t been normal for a long time.” It is in the nature of memoir to expect that Ritter will come to terms with the place, even grow to love it, and to some degree she does, but without in any way domesticating the land or its dangers.

Alternative: H. M. Tomlinson’s The Sea and the Jungle

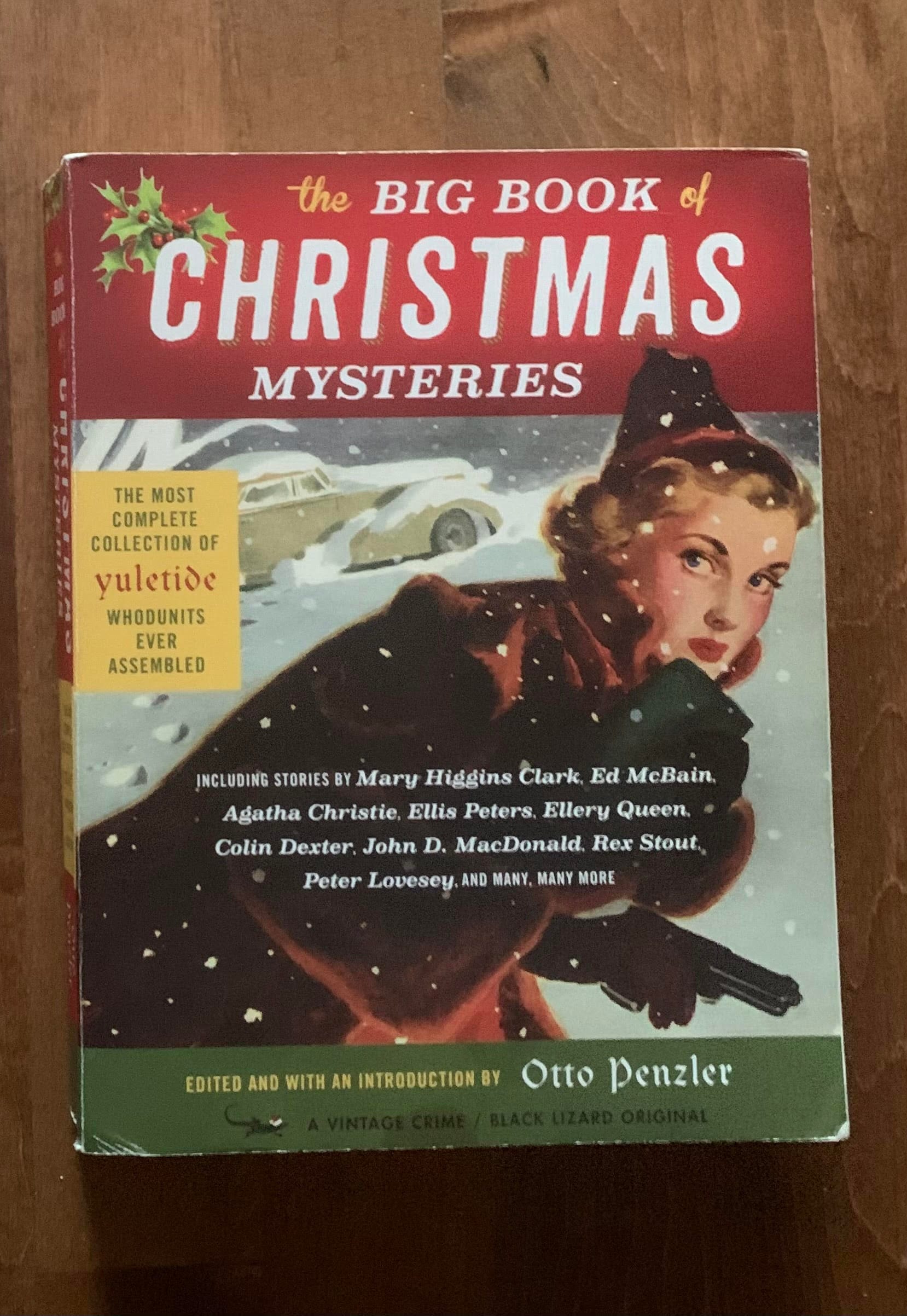

For your friend who has a good reading chair by their Christmas tree

The Big Book of Christmas Mysteries, edited by Otto Penzler (2013)

I always have a themed anthology of old mystery stories on the shelf to dip into when I’m between books. This one is particularly enjoyable, for what lends itself more to the imposition of order on chaos that is a mystery story than the well-structured Christmas season?

Alternative: Golden Age Christmas Mysteries, edited by Otto Penzler

For your friend who has read all of Barbara Pym, Anita Brookner, and Elizabeth Taylor

Elizabeth Jane Howard’s The Long View (1955)

Elizabeth Jane Howard has almost no presence in America, but I don’t think it’s unreasonable to rank her with the writers in the headline. All are interested in various aspects of the comedy and tragedy of domestic life. Howard is not as funny or dry as Pym, not as dark or cutting as Brookner, not as astringent as Taylor, but she shares some qualities with all of them, adding an appealing lightness of tone and an impressive ability to distill emotional relations into an epigrammatic sentence. This novel is cleverly structured, working backwards from the ashes of a relationship in a way that makes the later chapters genuinely moving. (If your friend reads and likes this one, turn them loose on her whole list. They won’t be disappointed.)

Alternative: Alison Lurie’s The War Between the Tates

For your friend won’t stop talking about Moby-Dick

Dan Beachy-Quick’s A Whaler’s Dictionary (2008)

Dan Beachy-Quick’s book, he promises in its introduction, “does not finish Ishmael’s failed cetological endeavor—it simply repeats the failure in a different guise.” You don’t need any more information than that, I promise.

Alternative: Paul Metcalf’s Genoa

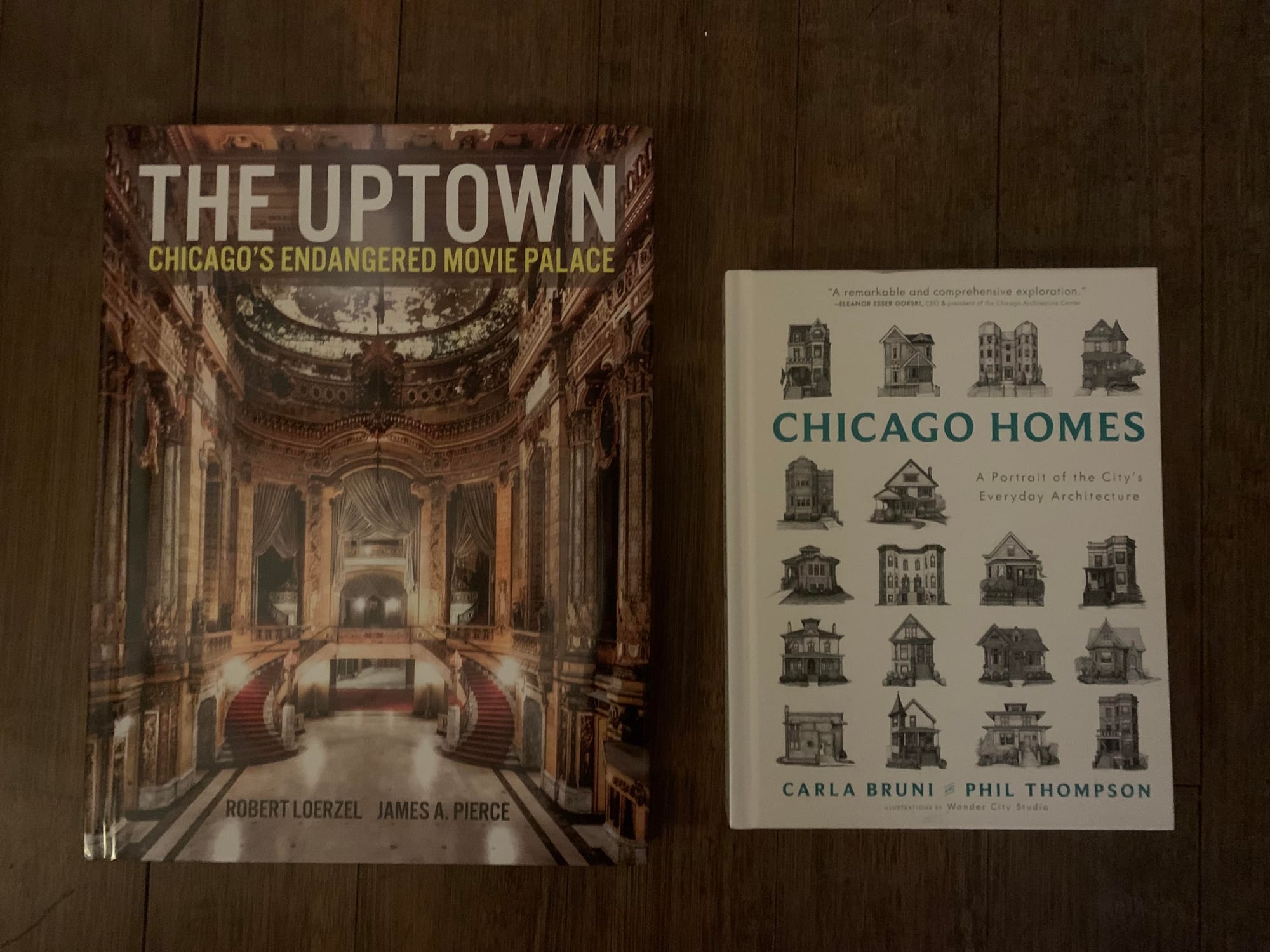

For your friends in Chicago

Robert Loerzel and James A. Pierce’s The Uptown: Chicago’s Endangered Movie Palace

Carla Bruni and Phil Thompson’s Chicago Homes: A Portrait of the City's Everyday Architecture

For fourteen years we lived around the corner from the shuttered Uptown Theater. Every once in a while the boarded-up front door would be open, a custodian standing in front of it. Behind him you could glimpse glory: Gold, red, terra-cotta, tile. Majesty. My memory of the custodian is that he was about as approachable as the guard in Kafka’s “Before the Law.” No one got in.

This book will suffice. It's full of gorgeous photos of this 4,300-seat 1925 movie palace, supplemented with a narrative history and images of historical records and ephemera.

Chicago Homes, meanwhile, tells the history of residential architecture in Chicago through its many recognizable building types, with line drawings to illustrate them. It’s all but impossible to not find a few here you’ve lived in, and immediately want to know more about them.

Alternative: David Quam's Brick of Chicago calendar

For your friend who spends too much (read: any) time on Nextdoor

Emily Cockayne’s Cheek by Jowl: A History of Neighbors (2012)

In the introduction to this very entertaining microhistory, Emily Cockayne suggests a definition of “neighbor” that one of her neighbors offered: “A neighbor is someone who you can visit in your slippers.” Which said neighbor was at that moment doing.

One of the the purposes this book can serve is to remind people that it can always be worse. For example:

Dunghills were heaped up wherever they could be contained, sometimes against the neighbour’s house. Rain saturated these stinking piles, encouraging damp to penetrate indoors and creating the potential for flooding. A London innkeeper heaped dung against his neighbour’s wall in 1677 and the moisture from it soaked through the wall “to the great damage and the Annoyance of her house.”

And also that some things have, alas, always been thus, as evidence of which I present this entry from the index:

Sex: hearing a neighbour having, 3, 197–8, 223; seeing a neighbour having, 14–16, 197; with a neighbour, 48, 72, 210–2

Alternative: Lars Iyer’s Nietzsche and the Burbs

For the friend you go to the rep cinema with

Hollywood: The Oral History (2022), edited by Jeanne Basinger and Sam Wasson

This book has all the problems of oral history: Questionable reliability, lack of context, unrepresentative participants. In addition, it has no index or notes, and even the biographical sketches of the participants are more brief than what your average fan of golden age Hollywood could deliver off the top of their head.

Nonetheless, if you love this subject, it’s utterly engrossing. Hoot Gibson tells about getting $2.50 for falling off a horse in the silent days. Leo McCarey says the problem with his original plan of being a lawyer was that, “I lost every case.” Raoul Walsh tells about how he hired an attractive woman to sit near Spencer Tracy on set and admire him, simply to keep Tracy from getting bored and stomping off. “Oh, I want the world,” says Bette Davis. If you like that kind of nugget, this is the book for you.

Alternative: George Sanders’s Memoirs of a Professional Cad

For your friend who has a little shelf of books they read from every morning

The English Year: From Diaries and Letters (1967), edited by Geoffrey Grigson

For every day of the year, this book offers a few lines from diaries or letters written on that day by English writers. We get both Wordsworths, Coleridge, D. H. Lawrence, Katherine Mansfield, Jane Austen, Thomas Hardy, John Clare, John Ruskin (“whose diaries mix egoism and petulance,” Geoffrey Grigson notes), and many more. The best of them is Gilbert White, whose descriptions of the turning of the year in the countryside are detailed and vivid, his updates on the doings of his garden turtle, Timothy, charming and sweet. On December 4, 1770, he noted that “most owls seem to hoot exactly in B flat.”

Alternative: Y’all know that Stacey and I edited The Daily Sherlock Holmes, right?