If there is an affirmative argument for the internet in this benighted decade, it's that it offers a chance for all of us to tip people off to things we think they'll enjoy. That's what I want to try here. Look at this, friends, not . . . all that.

The goal is to publish roughly every two weeks, alternating two types of issue. One will highlight a book, a movie, and some music. I'll try to include poetry regularly, too. Maybe once in a while I'll venture into visual art or other realms. For each, I'll give a little detail, but the issues will be brief. Because of this throat-clearing, this is almost certainly the longest I'll publish. The other type of issue will be a commonplace book, gathering quotes from recent reading that I think you'll enjoy.

Because I was a blogger for years and still miss the public, open nature of that method of publication, I'm also likely to try putting the contents of this newsletter on my old blog, I've Been Reading Lately. The idea is to meet readers where they are, in the format they prefer.

I may add a pay tier, though the content won't differ, simply because I believe in the general principle that you should pay for things you enjoy if you can. If you feel like subscribing that way, just know that I'll donate all the income from this newsletter to the Uptown People's Law Center.

Who am I?

I'm primarily a book person. My day job has since 1999 been at the University of Chicago Press, where I'm currently the marketing director of the books division. I've edited two books that I was fortunate enough to publish with my colleagues at Chicago: The Getaway Car: A Donald E. Westlake Nonfiction Miscellany and (coedited with my wife, Stacey Shintani) The Daily Sherlock Holmes: A Year of Quotes from the Case-Book of the World's Greatest Detective. I've been a Chicagoan for about 30 years now and intend that not to ever change. Regarding tastes: I'm an Anglophile and a fan of old Hollywood. I spend a lot of time with the cultural products of America between about 1920 and 1960 or so. In music I listen a lot to the vocal jazz and pop of the same era, but I also spend a fair amount of time with ambient music and current pop, plus I dabble in contemporary classical, and my youth involved classic rock and a mullet. To suss out my taste in reading, you couldn't do better than looking at the tags column on my old blog.

I'm pretty basic, to be frank. If you're engaged with culture, it's unlikely I'll often bring you things that are totally unfamiliar. Hopefully, however, I'll once in a while point you toward something you hadn't considered, or remind you of a forgotten favorite worth revisiting. Maybe you'll get to do the same for me someday.

Now let 's get to it.

Movie

Jewel Robbery (1932)

All discussion of the looks of film stars should be held in the context of what I've come to think of as the Buscemi Rule. The Buscemi Rule emerged from a story NPR host and podcaster Jesse Thorn told about interviewing Steve Buscemi and discovering that he is remarkably handsome. At risk of being rude: That is not the quality for which Buscemi is known. It's therefore a good reminder that even the most ordinary-looking person we see on screen would probably rank as one of the most extraordinarily beautiful people we might ever meet. The industry selects for beauty, and it's as ruthless a Darwinian niche as the darkest depths of the Mariana Trench.

Which brings us to William Powell. Who is not handsome. He's got baggy eyes and a weak chin and a long neck. His hair is unreliable. He's not strikingly built. He looked middle-aged even when he was young. You can tell at a glance that he would absolutely reek of cigarette smoke, like your Great-uncle Kenny staggering out of the Elks at 2 AM.

And yet . . . he's a star, and within a few seconds of watching him, we don't question it. He's charming. He's charismatic. He's light, and funny. His voice is both rich and soothing, an instrument for putting anyone at ease. He's exactly the right amount of ingratiating. His hands move in comfortable ways; they'd touch gently. The ineffable qualities that Hollywood has sought for more than a century are all there. Like Pedro Pascal, the most salient current example of punching above his looks, he makes you want to be his friend, to spend as much time as possible in his company.

Kay Francis, on the other hand, requires no such apologetics. She's gorgeous, setting pale skin strikingly against lustrous dark hair, and she marries that beauty to a smile that can shift in seconds from bemusement to surprise to seduction to joyful amusement. She holds her own when dealing with shovels of Marx Brothers nonsense or delicately delivering the delicacy of a Lubitsch line.

Speaking of Lubitsch: Jewel Robbery was released two months before Lubitsch's Trouble in Paradise, and it's trying hard to have the Lubitsch Touch. It doesn't; even Preston Sturges couldn't take that from the master. But it does have Lubitsch touches, beyond the wealthy, European setting: Some familiar framings, the use of quick cuts between close-up shots of objects to set the scene. And Kay Francis might as well be playing the same role as she does in Trouble in Paradise: A European socialite so wealthy that life is a game, a stance that in both films leads her to extend forbearance and eventually much more to suave criminals. Trouble in Paradise is one of the greatest films ever made. Jewel Robbery is not. But it does have enough of what we love in Lubitsch–including elegance, delicacy, cleverness, wit, and good casting top to bottom–to make it an excellent diversion for a summer evening.

(Interestingly, though Jewel Robbery is clearly a fantasy of a life beyond want, it nonetheless allows the Depression to peek through ever so slightly. A security guard assigned to a bank mentions that he's responsible for stopping robbers, not bank directors. Powell tells a store owner that once the insurance pays out, the owner should be grateful to him for turning all that inventory into cash, "in these times." Another character notes that it's good to see someone in Vienna have commercial success.)

Song

"Dynamite," by Taio Cruz

In the first verse of "Dynamite," Taio Cruz exults that at the club he's "wearing all my favorite brands, brands, brands, brands." I suspect I had a thought like that once or twice. In middle school.

In the second verse, Cruz rhymes "move" with "crew," then "do." Then "do" again. (Actually, it's "move, move, move, move," then "crew, crew, crew, crew," then "do, do, do, do.")

This is a stupid song.

But it's summer. We should all be a little stupid sometimes in the summer., and this is our last week to do so. This song, which reached #2 on the US charts back in 2010, has been a summer road trip go-to for me ever since. If you've not heard it in a while, cue it up as you head out of town for the long weekend and let its insistence on the beat and on the unimportance of anything else carry you along for three minutes. There will be plenty of time for autumn music on the return drive.

Cruz pronounces it "Din-oh-mite." That's fun.

Poetry

Robert Herrick

Most poets aren't remembered at all. Actually, scratch that. Most poets aren't even noticed. That's the nature of the work: You've chosen a medium that, outside of greeting cards and song lyrics, most people don't understand or are actively uncomfortable with.

Even those poets who wrote when poetry was the primary literary form, however, were more likely to sink into obscurity than to be known today. So when I say that you may not know Robert Herrick's name, but you do know one of his lines, that should be taken as saying that he's one of the lucky ones. Better one line than no lines. (Better a one-hit wonder, like Taio Cruz, than never to chart at all.)

This is the one you know, the opening line of "To the Virgins, to Make Much of Time":

Gather ye rosebuds while ye may

Herrick, a poet and cleric and Royalist in seventeenth-century England, is worth exploring well beyond that line. He wrote about 2,500 poems, many of them consisting of just a couplet or two. Compared to the work of his contemporaries, his poetry is pleasantly direct. He's often witty, even funny. He frequently aims for aphorism, and while he doesn't always hit, his engaging personality reliably comes through. Herrick feels less like he's performing than almost any other poet I can think of; he reminds me of Montaigne in how much of his passing thoughts and feelings make it to the page. In a recent New Yorker review of a new biography of another favorite poet of mine, James Schuyler, Dan Chiasson linked Schuyler's striking enjambment with Herrick's. Both use it to surprise and emphasize, to turn somewhat ordinary, sentence-like rhythms into something else.

I'll share two brief poems that suit our instant-reaction, politics-by-posting moment:

Posting to Printing

Let others to the Printing Presse run fast,

Since after death comes glory, Ile not haste.

Most Words, lesse Works

In desp'rate cases, all, or most are known

Commanders, few for execution

And I'll close with one that perhaps could serve as inspiration here in 2025/

Revenge

Mans disposition is for to requite

An injurie, before a benefite:

Thanksgiving is a burden, and a paine;

Revenge is pleasing to us, as our gaine.

Book

Dwyer Murphy's crime novels

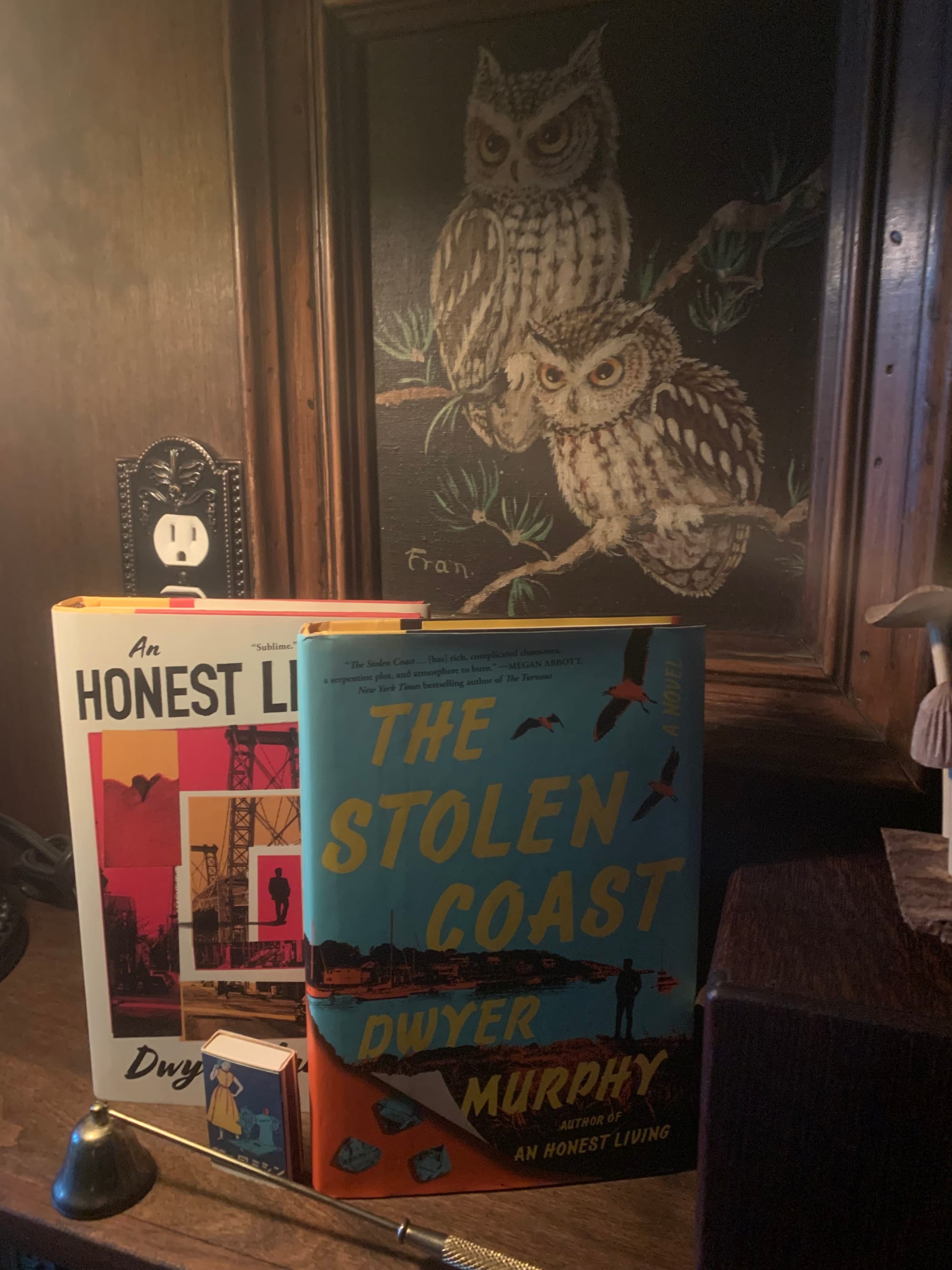

This post is too long already, so about books today I'll simply say that if your favorite thing about hard-boiled detective stories is not the plot but the detective's enervated attempts to push through his disillusion and world-weariness, the mistakes he makes in deciding once again to trust, and our knowledge that he won't learn from them, then Dwyer Murphy's An Honest Living and The Stolen Coast are for you. These novels breathe the air of Robert Altman's film of The Long Goodbye, though they're more humane. They're about people who've lost their way and have all but given up looking, but who spy what looks like one last chance. They're among my favorite crime novels of the century thus far.

(Dwyer Murphy has a new novel out, The House on Buzzards Bay, which is also worth your time and even stranger. Marketed as a thriller (because as I can tell you, you have to market a book as something) it is, as Rachel Hope Cleves noted on Bluesky recently, a lot closer to an experimental novel, full of meaning and allusion amid a reality that slips through our fingers as we try to examine it.)

Thanks for reading, friends.